PAM Authentication Modules¶

Prerequisites and Assumptions¶

- A non-critical Rocky Linux PC, server, or VM

- Root access

- Some existing Linux knowledge (would help a lot)

- A desire to learn about user and app authentication on Linux

- The ability to accept the consequences of your own actions

Introduction¶

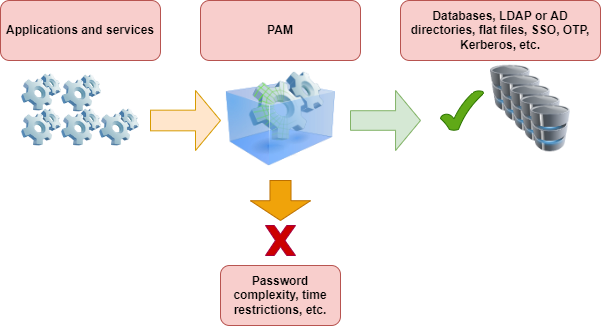

PAM (Pluggable Authentication Modules) is the system under GNU/Linux that allows many applications or services to authenticate users in a centralized fashion. To put it another way:

PAM is a library suite that allows a Linux system administrator to configure methods to authenticate users. It provides a flexible and centralized way to switch authentication methods for secured applications using configuration files instead of changing application code. - Wikipedia

This document is not designed to teach you exactly how to harden your machine. It is more of a reference guide to show you what PAM can do, and not what you should do.

Generalities¶

Authentication is the phase during which it is verified that you are the person you claim to be. The most common example is the password, but other forms of authentication exist.

Implementing a new authentication method should not require changes in source code for program or service configuration. This is why applications rely on PAM, which gives them the primitives* necessary to authenticate their users.

All the applications in a system can thus implement complex functionalities such as SSO (Single Sign On), OTP (One Time Password) or Kerberos in a completely transparent manner. A system administrator can choose exactly which authentication policy is to be used for a single application (e.g. to harden the SSH service) independently of the application.

Each application or service supporting PAM will have a corresponding configuration file in the /etc/pam.d/ directory. For example, the process login assigns the name /etc/pam.d/login to its configuration file.

* Primitives are literally the simplest elements of a program or language, allowing you to build more sophisticated and complex things on top of them.

Warning

A misconfigured instance of PAM can compromise the security of your whole system. If PAM is vulnerable, then the whole system is vulnerable. Make any changes with care.

Directives¶

A directive is used to set up an application for usage with PAM. Directives will follow this format:

mechanism [control] path-to-module [argument]

A directive (a complete line) is composed of a mechanism (auth, account, password or session), a success check (include, optional, required, ...), the path to the module and possibly arguments (like revoke for example).

Each PAM configuration file contains a set of directives. The module interface directives can be stacked or placed on top of each other. In fact, the order in which the modules are listed is very important to the authentication process.

For example, here's the config file /etc/pam.d/sudo:

#%PAM-1.0

auth include system-auth

account include system-auth

password include system-auth

session include system-auth

Mechanisms¶

auth - Authentication¶

This handles the authentication of the requester and establishes the rights of the account:

-

Usually authenticates with a password by comparing it to a value stored in a database, or by relying on an authentication server,

-

Establishes account settings: uid, gid, groups, and resource limits.

account - Account management¶

Checks that the requested account is available:

- Relates to the availability of the account for reasons other than authentication (e.g. for time restrictions).

session - Session management¶

Relates to session setup and termination:

- Performs tasks associated with session setup (e.g. logging),

- Performs tasks associated with session termination.

password - Password management¶

Used to modify the authentication token associated with an account (expiration or change):

- Changes the authentication token and possibly verifies that it is robust enough or has not already been used.

Control Indicators¶

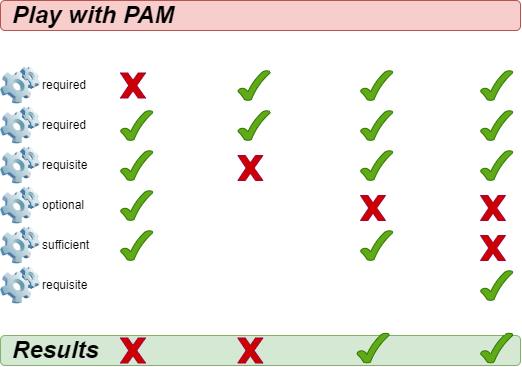

The PAM mechanisms (auth, account, session and password) indicate success or failure. The control flags (required, requisite, sufficient, optional) tell PAM how to handle this result.

required¶

Successful completion of all required modules is necessary.

-

If the module passes: The rest of the chain is executed. The request is allowed unless other modules fail.

-

If the module fails: The rest of the chain is executed. Finally the request is rejected.

The module must be successfully verified for the authentication to continue. If the verification of a module marked required fails, the user is not notified until all modules associated with that interface have been verified.

requisite¶

Successful completion of all requisite modules is necessary.

-

If the module passes: The rest of the chain is executed. The request is allowed unless other modules fail.

-

If the module fails: The request is immediately rejected.

The module must be successfully verified for authentication to continue. However, if the verification of a requisite-marked module fails, the user is immediately notified by a message indicating the failure of the first required or requisite module.

sufficient¶

Modules marked sufficient can be used to let a user in "early" under certain conditions:

-

If the module succeeds: The authentication request is immediately allowed if none of the previous modules failed.

-

If the module fails: The module is ignored. The rest of the chain is executed.

However, if a module check marked sufficient is successful, but modules marked required or requisite have failed their checks, the success of the sufficient module is ignored, and the request fails.

optional¶

The module is executed but the result of the request is ignored. If all modules in the chain were marked optional, all requests would always be accepted.

Conclusion¶

PAM modules¶

There are many modules for PAM. Here are the most common ones:

- pam_unix

- pam_ldap

- pam_wheel

- pam_cracklib

- pam_console

- pam_tally

- pam_securetty

- pam_nologin

- pam_limits

- pam_time

- pam_access

pam_unix¶

The pam_unix module allows you to manage the global authentication policy.

In /etc/pam.d/system-auth you might add:

password sufficient pam_unix.so sha512 nullok

Arguments are possible for this module:

nullok: in theauthmechanism allows an empty login password.sha512: in the password mechanism, defines the encryption algorithm.debug: sends information tosyslog.remember=n: Use this to remember the lastnpasswords used (works in conjunction with the/etc/security/opasswdfile, which is to be created by the administrator).

pam_cracklib¶

The pam_cracklib module allows you to test passwords.

In /etc/pam.d/password-auth add:

password sufficient pam_cracklib.so retry=2

This module uses the cracklib library to check the strength of a new password. It can also check that the new password is not built from the old one. It only affects the password mechanism.

By default this module checks the following aspects and rejects if this is the case:

- Is the new password from the dictionary?

- Is the new password a palindrome of the old one (e.g.: azerty <> ytreza)?

- Has the user only changed the password case (e.g.: azerty <>AzErTy)?

Possible arguments for this module:

retry=n: imposesnrequests (1` by default) for the new password.difok=n: imposes at leastncharacters (10by default), different from the old password. If half of the characters of the new password are different from the old one, the new password is validated.minlen=n: imposes a password ofn+1characters minimum. You cannot assign a minimum lower than 6 characters (the module is compiled this way).

Other possible arguments:

dcredit=-n: imposes a password containing at leastndigits,ucredit=-n: imposes a password containing at leastncapital letters,credit=-n: imposes a password containing at leastnlower case letters,ocredit=-n: imposes a password containing at leastnspecial characters.

pam_tally¶

The pam_tally module allows you to lock an account based on a number of unsuccessful login attempts.

The default config file for this module might look like: /etc/pam.d/system-auth:

auth required /lib/security/pam_tally.so onerr=fail no_magic_root

account required /lib/security/pam_tally.so deny=3 reset no_magic_root

The auth mechanism accepts or denies authentication and resets the counter.

The account mechanism increments the counter.

Some arguments of the pam_tally module include:

onerr=fail: increments the counter.deny=n: once the numbernof unsuccessful attempts is exceeded, the account is locked.no_magic_root: can be used to deny access to root-level services launched by daemons.- e.g. don't use this for

su.

- e.g. don't use this for

reset: resets the counter to 0 if the authentication is validated.lock_time=nsec: the account is locked fornseconds.

This module works together with the default file for unsuccessful attempts /var/log/faillog (which can be replaced by another file with the argument file=xxxx), and the associated command faillog.

Syntax of the faillog command:

faillog[-m n] |-u login][-r]

Options:

m: to define, in the command display, the maximum number of unsuccessful attempts,u: to specify a user,r: to unlock a user.

pam_time¶

The pam_time module allows you to limit the access times to services managed by PAM.

To activate it, edit /etc/pam.d/system-auth and add:

account required /lib/security/pam_time.so

The configuration is done in the /etc/security/time.conf file:

login ; * ; users ;MoTuWeThFr0800-2000

http ; * ; users ;Al0000-2400

The syntax of a directive is as follows:

services; ttys; users; times

In the following definitions, the logical list uses:

&: is the "and" logical.|: is the "or" logical.!: means negation, or "all except".*: is the wildcard character.

The columns correspond to:

services: a logical list of services managed by PAM that are also to be managed by this rulettys: a logical list of related devicesusers: logical list of users managed by the ruletimes: a logical list of authorized time slots

How to manage time slots:

- Days:

Mo,Tu,We,Th,Fr,Sa,Su,Wk, (Monday to Friday),Wd(Saturday and Sunday), andAl(Monday to Sunday) - The hourly range:

HHMM-HHMM - A repetition cancels the effect:

WkMo= all days of the week (M-F), minus Monday (repeat).

Examples:

- Bob, can login via a terminal every day between 07:00 and 09:00, except Wednesday:

login; tty*; bob; alth0700-0900

No login, terminal or remote, except root, every day of the week between 17:30 and 7:45 the next day:

login; tty* | pts/*; !root; !wk1730-0745

pam_nologin¶

The pam_nologin module disables all accounts except root:

In /etc/pam.d/login you'd put:

auth required pam_nologin.so

Only root can connect if the file /etc/nologin exists and is readable.

pam_wheel¶

The pam_wheel module allows you to limit the access to the su command to the members of the wheel group.

In /etc/pam.d/su you'd put:

auth required pam_wheel.so

The argument group=my_group limits the use of the su command to members of the group my_group

Note

If the group my_group is empty, then the su command is no longer available on the system, which forces the use of the sudo command.

pam_mount¶

The pam_mount module allows you to mount a volume for a user session.

In /etc/pam.d/system-auth you'd put:

auth optional pam_mount.so

password optional pam_mount.so

session optional pam_mount.so

Mount points are configured in the /etc/security/pam_mount.conf file:

<volume fstype="nfs" server="srv" path="/home/%(USER)" mountpoint="~" />

<volume user="bob" fstype="smbfs" server="filesrv" path="public" mountpoint="/public" />

Wrapping Up¶

By now, you should have a much better idea of what PAM can do, and how to make changes when needed. However, we must reiterate the importance of being very, very careful with any changes you make to PAM modules. You could lock yourself out of your system, or worse, let everyone else in.

We would strongly recommend testing all changes in an environment that can be easily reverted to a previous configuration. That said, have fun with it!

Author: Antoine Le Morvan

Contributors: Steven Spencer, Ezequiel Bruni, Ganna Zhyrnova